“I hated all the things I had toiled for under the sun, because I must leave them to the one who comes after me. And who knows whether that person will be wise or foolish? Yet they will have control over all the fruit of my toil into which I have poured my effort and skill under the sun. This too is meaningless. So my heart began to despair over all my toilsome labor under the sun. For a person may labor with wisdom, knowledge and skill, and then they must leave all they own to another who has not toiled for it. This too is meaningless and a great misfortune.” ― Ecclesiastes 2:18-21

When I first saw Alien³ I was awestruck at this dark, terrifying science fiction film that was somehow engaged with themes of moral and religious consequence, and above all, redemption. This was at odds with everything I had been warned about in horror films, which were just conduits for demonic possession. The alien creature was a monster, and maybe demonic, but the true evil was in the men who sought to control the thing―to weaponize it, to monetize it―and who gave not a whit about the human cost of such an endeavor. Yet in a type of hell on a prison planet among the worst criminals and convicts in the universe, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley sacrifices herself to save those troubled souls and maybe the rest of humanity itself. This was wrestling with some deep themes, and hardly the pagan celebration of horror and gore I had been led to expect.But then I was faced with another set of confounding opinions. Critics hated it. It wasn’t until much later when I final saw the original Alien and it’s first sequel Aliens, that I began to get a sense of why people hated the third film. Ripley, having survived the initial encounter with a Xenomorph in the first film and then thrown into an ill-fated rescue and reconnaissance mission in the second, had found some resolution and sense of family in it all through her protection and, for all intents and purposes, adoption of the girl Newt. Alien³ begins by erasing all of that, killing off Newt and the other survivors of the second film and stranding Ripley on the prison planet with yet more Xenomorphs to confront.

In a way, all the challenges Ripley had faced and overcome, and all the resolution she had worked for was gone. All the work done by the filmmakers, Ridley Scott and James Cameron, had led to this, a reset of circumstances. The only thing Ripley and audiences had was the experiences of having been through it.

I say all of that to set the stage for Avengers: Infinity War, whose cold opening seemingly does the same thing to Thor (Chris Hemsworth) that Alien³ did to Ripley. In Thor: Ragnarok, Thor makes the bold move of sacrificing Asgard to save who is left of its people and a few ragtag stragglers from The Grandmaster’s gladiator arena. By the end of the film, it’s also seemingly done that to Black Panther’s Wakanda, the Guardians of the Galaxy franchise, Doctor Strange, Spider-Man, and a whole host of other characters we have invested in over the course of 18 films set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU).

This erasure of character and narrative advancement is nothing new in the MCU. Avengers: Age of Ultron dispassionately ignored Tony Stark’s (Robert Downey Jr.) promise to Pepper Potts (Gwyneth Paltrow) to retire the Iron Man suit at the end of Iron Man 3, for example. Joss Whedon, who wrote and directed the first two Avengers films famously fell out with Marvel and noted the experience of working on the second film “broke” him as he tried to create his vision, ignoring plot elements from different MCU films and TV series (including the resurrection of Agent Coulson on Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., who he had killed in the first film).

One also expects―in part because of the very nature of the Disney owned Marvel studios is to produce more, more, more―that much, if not all, of what is erased here will itself be erased in upcoming MCU films. But with or without the corporate entity behind the production of the MCU canon, these characters and stories including them will go on, inherited by fans, artists, critics, and school children.

“The Marvel Universe … was a work of fan fiction. It was fans-turned-writers who decided they liked cohesiveness, continuity, and putting all the characters into big epic battles.” ― Jeet Heer

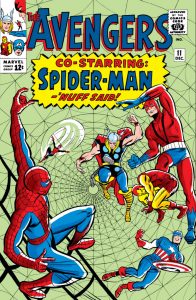

The origins of superheroes lie in serialized formats, from penny dreadfuls to pulp magazines which featured short, ongoing chapters in various hero’s adventures on to dedicated comic titles featuring a single hero and then to radio shows and film serials which played before features. What eventually helped make DC and Marvel Comics the media giants they became is the crossover events and world building that came from the second and third generation comic creators. They were marketing gimmicks to be sure, but they turned out to be more than just a way to sell more copies of magazines. Readers enjoyed seeing Spider-Man interact with the Fantastic Four and the Avengers and the X-Men.But eventually comic authors became frustrated not being able to tell contained stories―sometimes with characters they created themselves―that wouldn’t fit into the shared world the characters had now come to inhabit. Readers too became frustrated having to buy titles they didn’t normally follow to keep up with storyline details. And ultimately, the worlds began to collapse under their own weight. Both DC and Marvel Comics have rebooted their universes, introduced different timelines, different universes, and reimagined their characters so many times it’s impossible to reconcile it all into a coherent, shared world, the very thing its architects set out to create.

Now, these shared universes have switched mediums. Except instead of a motley group of artists, writers, and promoters at the shit end of the publishing world, they’re being created and distributed by those in charge of the largest media companies in the world. And despite ten years of MCU films, this is still a new type of storytelling in the cinematic medium and both critics and audiences are split over the merits of massive crossover events between various franchises.

For better or worse, Infinity War has centered the crossover on Thanos (Josh Brolin), the film’s villain―a choice that is unique so far in the MCU―and allowed most of the heavy lifting of character development of the heroes to their respective franchises. It’s a different category, not just genre, of film. But while this may vex viewers expecting a self-contained story with loose ends tied up from previous films and clear character arc growth, it succeeds wildly at being a tonal and thematic focal point for the films that do focus more on the individual heroes.

“They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry, as do all [others]; they beget children; but they do not destroy their offspring.” ― The Epistle to Diognetus

Avengers: Infinity War is the darkest MCU film by a wide margin but manages to retain the sense of humor that has infused much of the rest of the installments. Nothing better capsulizes this than an exchange between Thor and Rocket Racoon (voiced by Bradley Cooper). Rocket, we know from the Guardians films knows a thing or two about covering pain with inflated boasting, senses Thor’s pain despite his focus on a mission to find a weapon powerful enough to kill Thanos. Upon questioning, Thor admits if he fails, what else is there to lose? The exchange is heartfelt, funny, and it works between two characters who have only spent a couple of minutes of screen time together because we are so familiar with them from their other appearances.

Among what Thor has lost―including his people, friends, mother, and brother Loki (Tom Hiddleston) ―was his father Odin. But in his loss of Odin, Thor also discovered his father had not always been the noble and wise king he had thought. Odin had acquired much of his lands through violent and barbaric means.

Elsewhere throughout the MCU, we encounter characters coming to terms and dealing with their fathers―or their lack of them―in one form or another. Similar to Thor; T’Challa, the Black Panther (Chadwick Boseman) wrestles with a villain his father helped create by abandonment; Tony Stark deals with jealousy of Steve Rogers, Captain America (Chris Evans) who his father seemed to value more than his own son and also tries to be a surrogate father figure to Peter Parker, Spider-Man (Tom Holland); Peter Quill, Star-Lord’s (Chris Pratt) father only wanted his son for the power to be able to recreate the universe in his own image; Scott Lang, Ant-Man and Clint Barton, Hawkeye, both notably absent from this film, struggle to be good fathers while dealing with their own personal demons; and of course, Gamora (Zoe Saldana) and Nebula (Karen Gillan), whose father is Thanos.

Unlike his portrayal in the comics as a being interested in literally courting the female embodiment of death, here Thanos acts out of a perceived sense of conservation. Reasoning that the universe is finite and eventual wars over resources will decimate everyone as it was playing out on his planet, his aim in acquiring the Infinity Stones is to wipe out half the life in the universe, like a form of extreme population control. Or, to put it another way, Thanos means to bring peace through violence, compliance through force. And he’s perfectly willing to do so by destroying his own children.

In order to gain one of the Infinity Stones, Thanos travels to a mountaintop with Gamora and is told he must sacrifice something he loves. Like a dark mirror version of the story of Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac, where instead of faith that God would provide a sacrifice in place of his son, Thanos places faith only in himself and his will, and instead of an angel of the Lord to stay his hand, only the Red Skull. Gamora, for her part, is at first relived, thinking there is nothing Thanos loves to sacrifice. But of course even monsters love, even if it is a disordered love, and so she is destroyed at the hand of her father.

Dr. Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch), protector of the Time Stone, at one point echoes Thanos’ sense of conservation and protection by means of force, warning he would not lift a finger to save a conflicted Tony Stark or Peter Parker if it meant losing the stone to Thanos. Stark, of course, has been wrestling with this idea ever since he realized he couldn’t save the world by himself after the first Avengers film and his experimental defense system turned weapon that was Ultron. Steve Rogers, at a different time and in a different place asserts they will not trade lives. In the end though, Strange offers up the stone willingly to Thanos, saving Stark, if not Parker, trading lives and sacrificing himself in the process.

Before her death, Gamora argues with Thanos, saying he cannot pass judgement on billions of people―he does not know they will end in violence against each other competing for resources. He responds he is the only one who knows this. Unable to comprehend the redemptive nature of sacrifice, or the idea that people can choose not to act in violence, Thanos completes his work and leaves a shattered universe where seemingly every bit of resolution or character development these heroes have struggled for is blown away like dust in the wind.

But the work of evildoers is as meaningless as much as the work of the good. And those who have lost everything still have something left: memories and experience. Maybe sometimes it is wise look forward to the erasing of work and the struggle of starting over after everything is lost.