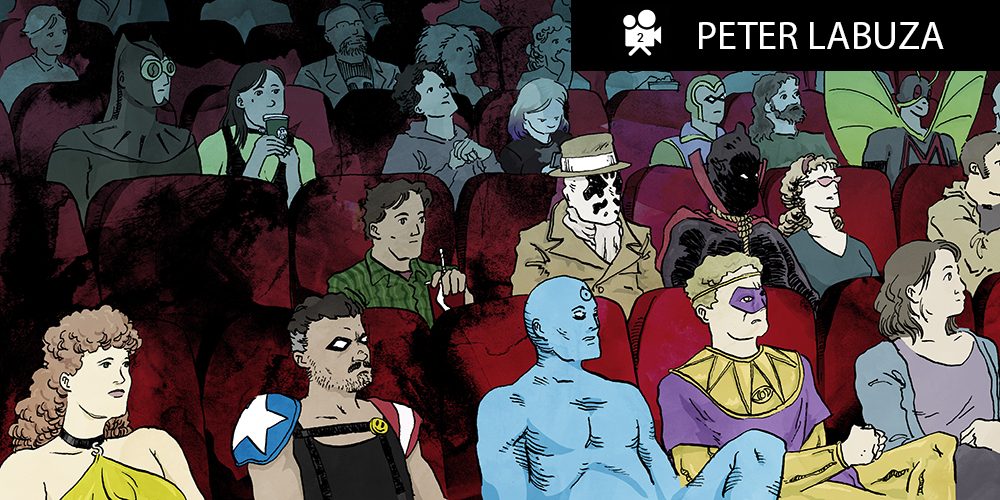

Illustration by Seth T. Hahne

I had the opportunity to sit down with Peter Labuza, host of The Cinephiliacs podcast, sometime film critic, and now film historian looking at the legal history of Hollywood, for our second installment of Who Watches the Watchmen?Peter is an apropos guest, having begun his career in film criticism with a DIY website and podcast that interviewed critics. Since then he’s delved into classic Hollywood and world cinema, a historian as much as a critic, and has become a singular voice in bringing cultural discussion to films, and the people who made them, that may have otherwise have been relegated to the dustbin of history.

This interview was wide ranging and has been edited for length and clarity, but one thing that I hope comes through–although it’s hard to convey in text–is Peter’s unbridled enthusiasm. He is a pure joy to talk to and full of curiosity as much as observation.

RUD: Thank you for agreeing to let us ask you a few questions. Can you tell us a little about your history writing on film and your podcast?

Labuza: I think like a lot of people of my generation, I started as a blogger. I was just running an amateur website. I started mine all the way back in high school. It was more for my own benefit to work through writing ideas about movies I had started to become interested in. The writing was very poor–I was in high school–this was not something I was very good at. I just kept doing it for a decade or so and kept working at it and working at it. Then I became the film critic at the newspaper in college–that would be the Columbia Spectator at Columbia University. And I was an editor there, and like anything else, that helps train you, college essay writing helps train you. I was able to take a lot of those skills and apply them to writing movie reviews.

The first sort of real work I did that had a monetary value associated with it was a video essay I did on Certified Copy, the Abbas Kiarostami film. I had done it for my own interest, my own purpose. I was sort of interested in how video essays worked. And Matt Zoller Seitz, who was running this video essay website called Press Play at the time, saw it, really liked it, and said, “Hey, take it off of Vimeo, put my logo on it and I’ll send you $50.” Mostly I liked the idea that it was posted on this website that had a lot of incredible work associated with it. I think from there I just did a couple more video essays. A couple people noticed my work. They noticed me on social media like Twitter and I was sort of able to get some various writing gigs at Little White Lies, Indie Wire, and a few other websites.

I started the podcast around the same time I was getting those writing gigs. Podcasts were becoming a thing. The Filmspotting podcast was very, very popular at the time. And I was fascinated by the Marc Maron podcast, WTF. Particularly the early episodes. I think it had this interesting dynamic where he views himself as a failed comic. And he’s talking to other comics who had made it. And it’s very much inside baseball. They were talking about form, technique–the things that only they knew. And I found it really interesting as an interview format because it was so different from someone like Charlie Rose or Terry Gross–people who don’t usually know that much about what they’re talking about, or who don’t know it in the same way. They’re very intelligent interviewers, but they’re approaching it as an outsider. What I thought was interesting about the Marc Maron format was it was an insider talking to another insider. So I knew Matt Zoller Seitz and I knew a couple other critics and I sent an email and asked if I started this, would you guys guest on some of the first episodes I do? And it launched in July 2012 and I’ve just tried to keep doing it every few weeks and it hasn’t stopped.

RUD: You’ve moved into an interesting space, I think, in film criticism and writing. You’re looking at some of the more esoteric elements of the art, from classic films to telling the story of Hollywood through the legal history of cinema. Why do you feel it is important to look in these places that a lot of other people might find disinteresting or ignore?

Labuza: I think I was always fascinated by questions like, how did this movie get made? And I think there’s been a lot of great histories written over the years that try and answer those questions. I know like, Thomas Schatz’s Genius in The System is one of the all-time great books about studio history. Mark Harris’ book, Pictures at a Revolution, is a very good example of someone who is doing sort of a cultural history with oral histories.

But I think I had always been fascinated by older films. Films from either time periods or cultures, or intellectual spaces, that I didn’t necessarily understand. And I wanted to understand. I wanted to look at some of the films and eras that I was interested in, but I also wanted to look at some of the myths that got built around those eras. There was a lot of discourse around the time I was beginning this that the golden age of television that we live in now–the sort of Mad Men, post Sopranos era–is very similar to what the New Hollywood of the 60s and 70s represented. But the more and more movies you see, you get this weird sense the New Hollywood was not this huge, diverse, unique system. We’re really only talking about 20 or 30 films.

So, I was really curious, how did that get built? Both culturally and as a business. And why does everyone talk about, “oh man, it was so good back then.” What was so good? And to get to that I followed the archives. I got really interested in looking at archival sources. I think that is fascinating. You look at the correspondences between the moguls. You look at the production sheets that said how many shots they did every day. You look at the notes on scripts. You look at the censorship materials. I think all these things are very fascinating and tell us a lot about how any sort of system worked. And what I found was that nobody else had really looked at the contracts.

I just found this amazing Joan Didion quote, that I’m absolutely using in my research now as sort of an epigraph. She says if you want to understand any movie, don’t look at the screenplay, look at the deal memo. And my heart just lit up when I read that. And I think that says a lot about this era of how Hollywood worked. I think it’s always important to look at the background in any sort of contemporary or historical era.

You don’t necessarily have to do it through legal history. There’s great cultural histories, there’s great histories through social mobility or the history of aesthetics. I think for me, it’s really important to look at legal history. I think we’re in a moment now where we are beginning to understand how laws affect our everyday life and I think that’s just as true of movie industry history as it is for contemporary society.

RUD: I was listening to your 100th episode of your podcast, where the tables were flipped and some of your previous guests got to ask you questions, and at a couple points you brought up viewing things like educational videos and even police body cam videos as types of cinema. Do you think it’s important to look at all recorded video through that critical lens?

Labuza: Oh, definitely! I think it’s hugely important. And this would fall under a larger field that I think academic studies would be called media literacy, right? And it’s to understand–I think for a lot of us this is the big question of watching CNN or Fox News and thinking about what quote-unquote constitutes fake news.

But more than that, I was thinking about this because I was home a couple months ago and my dad had turned on the news 24 hours a day. And once you start to understand how CNN works as an aesthetic experience, you start to understand the news in an entirely different way. More than just the content they’re delivering, you start to look at how they’re delivering content: how the ads are placed, what are their repetitions, what are their beats, how the anchors approach certain topics, what moments they start to try and build as these dramatic narrative points around the stories they are doing. It’s very, very revealing, and very scary. It helps you understand how a company like CNN or Fox works.

Now, I think the same things goes toward historical education films. These were aesthetic experiences that were designed to deliver ideas and content in a way that sometimes that is both thrilling and exciting but also, they’re trying to figure out how to deliver it. I was just in Indiana doing some research and there was a set of films made in the late 1950s about traffic court. These were films made for judges who worked in traffic courts. They actually star Stacy Keach, Sr. who is the father of Stacy Keach from Fat City and a lot of other great films. But what I found interesting was how they used this sort of aesthetic world to tell us and teach us about the role that traffic court lawyers played in American society. And the ways that they talk about this visually are just as important as the ideas that they are building. I think it’s something to be careful of. It’s not about saying we need to appreciate this as an aesthetic object. But the ideas and questions that we bring as people who study the aesthetics of film can tell you a lot about the questions that we as a society might ask.

I think so much about the Rodney King footage in that same way. How it’s from this old VHS camera, it’s from this point of view that looks from one angle. I think it’s… that police body camera footage is very harrowing to watch. And I don’t really recommend anyone watch it. I don’t know who can derive pleasure from it certainly. But I think what’s important is where the camera looks and how the camera looks. And that tells so much about the sort of reality that’s being caught by those images. And that is important to think about and consider when we’re looking at media as we enter a more and more media saturated 21st century–asking the questions of more than simply what is onscreen.

RUD: I was reading a lengthy article on The Blacklist the other day about the few remaining video stores left. And it got into talking about streaming services that have so much recent content but very little classic content and how a lot of films are stuck in licensing limbo and may never see the light of day again. With so much current content available, why is it important to preserve and watch older films?

Labuza: I think for me, on just sort of a gut level, that is what I get pleasure from the most. Both pleasure from that sort of aesthetic and pleasure from the sense of discovery. The problem is, if I can be a little honest, whenever I go to a new movie today–and I’m talking about whether it’s a Hollywood blockbuster or a prestige indie film or, frankly, even a lot of the art cinema films being made–is there’s no surprises. I feel no surprises narratively, I feel no surprises aesthetically. Everything just resembles the last object I saw from that vein. I think that is frustrating.

That’s the surprising thing with the classical Hollywood system. It was designed in a very, very–I’m oversimplifying–but like a Ford Factory model. It had its inputs, it went along an assembly line, and it delivered a specific type of product. But there’s a lot of ingenuity there. And there were a lot of ways that people tried to make that product interesting. I think the more we discover, the more weird and interesting and things you didn’t expect exist. I think people should just watch what they want to watch. But I think they’ll be kind of surprised by the kind of material that’s out there.

I was just corresponding with a friend who came from the San Francisco Silent Film Fest. And one of the films that they played this year was a film from the late Soviet Union from 1929 or so. I think we think about Soviet film from the late silent and early sound era as being essentially Communist propaganda. I love Man with a Movie Camera, it’s one of my all-time favorite films. It makes me want to go join the collective immediately after I watch it. But what was a surprise was that last year’s film, a Ukranian film called Two Days, and this year’s film–films that were made under the same studios that produced Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov–were much more critical, or at least ambivalent, about what we might call the vision for the Soviet Union.

Two Days was made in a melodramatic style that we might associate with a film like D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. It was inventive, but not inventive in the same way that we think of the Soviet Union film system. When I saw that, I thought, maybe I don’t understand as much about Soviet film style and studio history as I thought I did. Because there seems to be a much more complex set of values both aesthetically and politically happening here. And that’s the thing that I always want when I go to films and why I’m so often going to older films. I’m always finding surprises somewhere or in something.

RUD: Listening to you, I’m thinking about the phrase, “history is written by the winners.” And I’m wondering if all these older films that aren’t part of the traditional canon still have value. They certainly had an effect on the people making them and audiences that saw them at the time. Do you think it’s important to excavate these films that aren’t part of the current popular consciousness?

Labuza: Oh, definitely! I think that’s one of the most important things we can do. We’re not Taking away Citizen Kane. Citizen Kane is still wonderful. Vertigo is still wonderful. All these films are still wonderful. But we also want to expand the canon and make it more interesting. I think there’s just so much incredible work that could easily be placed in the same sort of spaces.

I think I have a good example. Last year there was this huge program that was put together by the Getty and some other partner institutions that was celebrating Latino art and particularly different forms of Chicano and Latin American art through the Latin American community in Los Angeles. And part of that was a series put together by UCLA and the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences and a few other partners that showed 38 films in East Los Angeles where the Chicano cinemas were–where the old Spanish language speaking cinemas were. And this was the combination of some Mexican films that people might know like María Candelaria or Dracula–there was this Spanish language version of Dracula made in 1931 that shot at night while the Tod Browning film shot in the day. But there were also Argentinian films, Cuban films, and films that were made in Hollywood that were Spanish language from 1930 to 1960.

What I felt was really interesting while I was watching them–I saw about 30 of them, I watched as much as I could–was that I could teach the history of classical Hollywood without showing a single film made in Hollywood. I could just focus on the same issues of stardom, of classical style, of genre, of narrative, by focusing on works that were made in Argentina and China and Japan and what have you. And I could teach everything I want to teach in the same way. And I think it shows something more when you do that.

I think that’s the thing about the canon. The more you expand, the more ideas you can bring into it. And some of those ideas are exciting and new. And I think getting to this point–Kristin Thompson said this many years ago, and I think it’s a very important point–is the reason we watch and teach Citizen Kane is that it’s a very easy film to teach a lot of important things that we want to talk about when it comes to how movies are made, or that you want to introduce someone who is new to film to. Whether or not it’s a great film, it’s very easy to teach what’s there. I think these other films are out there where you can teach not only the same things but a lot of new things.

And I’ve seen films get added to the canon. I think the people of Milestone Films are a good example of people who are very good at building a system that gets films inserted in the canon. It has been about ten years ago now that Killer of Sheep got a new release on the big screen and got an accessible DVD that film studies classes could buy, that regular people could buy. Now everyone admits Killer of Sheep is part of the cannon. It is there. I think we’re going to see the same thing with Milestone’s recent release–I think now maybe a year ago–of Losing Ground, the Kathleen Collins film. She was an African American director working in the 1980s in New York. I think it’s an example of a film that in 5, 10 years from now we’ll say, of course it’s part of the cannon. It’s a canonical film. It belongs there because it’s so aesthetically radical and so interested in a point of view of the world that doesn’t get told much. I think these are just exciting things.

I don’t think we’re losing Vertigo anytime soon. We’re just finding better movies to talk about in addition to Vertigo.

RUD: Throughout history, we’ve always told each other stories and interpreted them. Film is another way of doing that. Do you feel that film is more than just entertainment? What is the point of criticism?

Labuza: That’s a tough one. Especially if we take people’s interest in entertainment seriously. Which I think we need to do. There’s one vein of criticism that takes entertainment and elevates it to art and that’s seen as a very, very important way to bring a seriousness to the movies. This is a problem that goes back to–you read the criticism that is being written in 1897, 1898 when cinema is just being born, and people are already trying to do this. They are saying, no, no, it’s more than entertainment, it’s this total art form, it’s a spiritual thing. I think there’s a worry that you need to take this thing that was designed essentially as a mass art–particularly for lower classes–and say, no, this is important, it’s serious.

And certainly, I think the market for film has sort of turned that out. And increasingly in our contemporary moment you see more and more film artists who used to make films for Cannes are going to gallery spaces and trying to be taken more seriously as artists. But I think the thing with criticism is that it can do a lot of things. It can have a lot of functions. I think some of the problems with contemporary criticism is sometimes it’s the lowest common denominator of work that seems to be–I mean, I hate to say this, but I think a lot of times you see what I call the repackaged press release. That the critic is essentially just doing the work of the studio.

That doesn’t mean you can’t say I really, really like this film, go see it. But I hope that the criticism does more than just serve the studio’s need to get people into seats. I think this is a very scary problem. And a problem that you see with what people call the “identity first” person who says this film reflected my interests as a person and fits this particular demographic and that’s why it’s so important.

I want to be clear. I I think there is amazing work and criticism to done that looks at films through the lens of their particular social group that they are writing for. But I think really good criticism opens up and asks larger questions than just serving what the studio might want. I think a very, very good example is the critic K. Austin Collins who is now at Vanity Fair but was at the Ringer and wrote a piece about Love, Simon. And as a queer critic he was really looking at how these queer films are made. Are they even being made for me? It doesn’t seem like they are made in a way that is supposed to appeal to what I believe in or what I want. But where does that leave me? It was an absolutely incredible essay.

So I think the idea, with any criticism, whether you’re just looking at aesthetics, whether you’re looking at identity, at politics, whatever, is that you want the film to open up in a different way. I mean, one of the things I like reading is how you get out of a film and you just you want more. And you want it to open up in a different way or in a way that speaks to you that you didn’t think about yourself. That’s exciting. What I hope to convey to other people who think that film is just entertainment is that you can get pleasure out of reading about films or television or media or whatever. That reading brings you a certain about of pleasure in learning more about it in a different way. And I think that’s the most important thing a critic can do.

For me, that often means writing about films historically, placing it in a narrative that explains that this film was made at this particular studio and this is what was going on at this studio and they were using this production process and system. And it’s interesting or unique that the film exists in the way it does because of certain rules and regulations at the studio allowed it to be made in a surprising way. Something like that. That’s the work I try and do, and I’m glad that there are other people doing other work. I don’t want to represent all criticism. I want to represent my little sliver.

RUD: What you said about some criticism being a prepackaged press release, I think that is something that a lot of audiences react to negatively. They don’t feel that criticism is doing anything other than being a sales pitch.

Labuza: I think Roger Ebert put it really, really well years ago where he talked about the difference between film reviewing and film criticism. He said film reviews are for before you see the movie and film criticism is for after you see a movie. For the most part, I think cinephiles have a pretty good sense of movies we’re going to see and which one’s we’re not going to see.

I don’t mean to be obvious, but like I’ll say to myself, OK, I’m probably going to skip Deadpool 2 and maybe I will see… I’m going to go see Ray Meets Helen, which was this film that got a tiny, tiny release but is directed by Alan Rudolph who has always been one of my favorite filmmakers. I don’t need someone to tell me whether I should go see Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom. I’ll text a couple friends who are full time critics and I’ll ask, is there anything interesting in this film that I might want to go see? Because seeing the Hollywood blockbusters is important. They tell us something about the way that Hollywood thinks about itself and what they think audiences want to see. But I think the difference between film reviewing and film criticism is a blurred line in a lot of ways. And I think the best people find ways to meld those together.

But I think one of the interesting things you’ve seen, especially in the last 5 to 10 years on the internet is a lot more pieces now about the post discussion. I think the reason that took off was “we need to explain to you about the post credit scene in the last Marvel film so you can know about the next Marvel film.” Which is exactly what the studio wants you to do. But I think occasionally you see really interesting discusions. Like around The Last Jedi, the last Star Wars movie, that prompted a lot of questions because it brought up so many interesting, unique aspects of a world that seemed very, very tired and very, very dull. And then people went on to write about it because it’s a different way of articulating this franchise that we all know and love.

RUD: I think it’s interesting to get a glimpse of the worldview of critics because it informs the perspective they write from. Do you believe we live in a benevolent universe or an uncaring universe or a hostile one? Do you think art speaks to anything enduring or is it just an impermanent connection?

Labuza: Wow. Well, we live in truly perilous times. I’m not the first one to maybe point that out. I think for some of us, art brings a little bit of pleasure and comfort and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with escapism. I also think it’s really fascinating when we explore art that brings us closer and makes us see the world in different ways. It’s cliché, but I think there’s exciting things about seeing films that take place in certain unknown-to-us areas of the world like China.

We mentioned before we started interviewing Anthony Bourdain passed. And that’s someone who really wanted to know about everything in the world and explore it. The universe is… there. It exists. We’re… I think if all of us in this world can do a little good, bring a little pleasure, help people out and make life more comforting, especially given the vast ranges of inequality that exist… I think that’s something good we can do. And I think there are many, many different ways people can articulate that.

For me, that’s writing about films that give me pleasure and that give other people pleasure. But I think that’s also what I try to do with my research in legal history. It’s important to understand the industry through understanding labor. And labor inequality. I mean, it’s a huge part of the questions I’m answering. It’s about how does inequality get built and why does it get built? And where do people seem to break through and how are they breaking through? And I think that’s really, really important.

When I finish the book that will eventually come of this whole legal history question, I want it to work as both an entertaining story but also a guide to help people think about how the industry got built and how do we break it. That’s exciting for me to feel like that might be valuable.

I mean, it’s “take your pleasure.” I do a lot of cooking. I really like cooking. That brings me pleasure and makes life a little easier to live, but I think it’s important for all of us to figure out how can we contribute to this greater world that we have to be a part of.

RUD: Is there a film, not necessarily your favorite, that you look forward to sharing with others who haven’t seen?

Labuza: That’s tricky. I always tell people you should watch what you want to watch. I don’t know if I do a lot of advocacy for film or not. I do find it important and interesting, but I think there are better people who are better at advocating. But I’ll just point out two recent examples of two films that I want more people to see because I think they represent sort of the best of what the contemporary cinema can do

Cameraperson, the Kirsten Johnson documentary from 2016, which I think was one of the most exciting, unique films about someone who uses their camera to reach out to the world and show it, but also show something about themselves. It’s just and incredible look at what a camera can do to a person and to a world.

The other would be Magic Mike XXL, starring Channing Tatum. It had music, dance, and like man, that film was utopia. I saw that in theaters and I was just like, I am in church somewhere, like I don’t know what’s going on. It’s incredible. Like, you go into Magic Mike XXL and you think, OK, I saw the first one. This is going to be a silly, fun, maybe a little dour stripper film. And instead you get this film that is just the most happy-go-lucky film you could possibly imagine. But it’s also showing us a better world that could exist. And I think that’s exciting.

I think those are just two exciting films that do something completely different than a lot of the films that get regular releases these days.