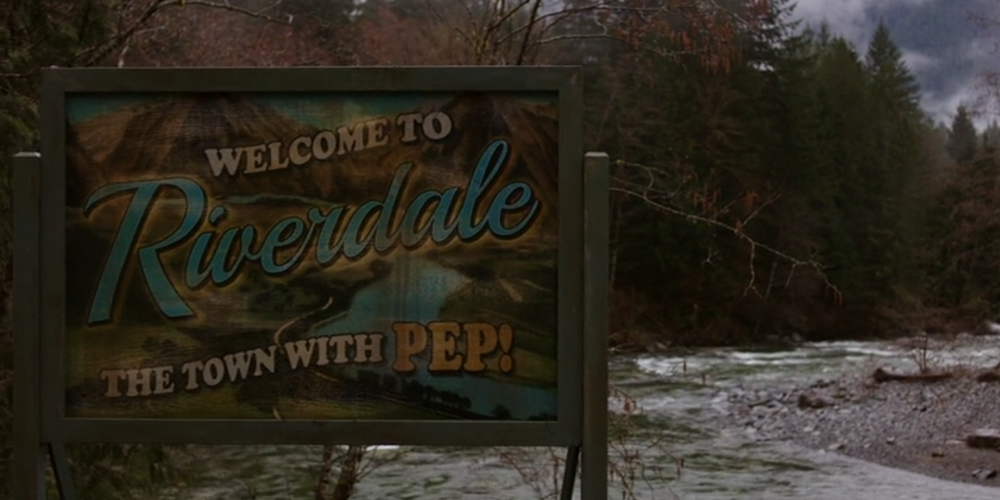

We should be clear about this: Riverdale is absolute stone-cold trash. The acting (outside of a few veteran standouts, mostly playing parents) is hardly more than adequate. The plotting is so over-the-top that it’s a challenge to know at any time who is supposed to like or hate whom (Cheryl Blossom is particularly confusing in this regard). The dialogue is mostly terrible (“You look like a dream warrior from A Nightmare on Elm Street 3,” says Jughead at one point). This is, frankly, not a show to recommend without a huge warning that liking it probably says more about you than it does about the show itself.

Riverdale is also the perfect Archie adaptation. As Bart Beaty observes in Twelve-Cent Archie, the Archie comics have never been about consistent characterization—or about characterization at all:

Archie Andrews is an atypical comic-book protagonist. He is a young man to whom things happen; he is not someone who makes things happen. Only rarely is he the central actor in any of the plots in which he is involved. Only on occasion is he the character who takes the first action. In character terms, he is actually little more than a cipher—a blank space on which stories are written. (16)

This is perfectly replicated in the show itself, where Archie is little more than a gorgeous hunk whose job is to look pretty and perplexed at all the insane stuff going on around him. He certainly isn’t terribly effective when he gets involved in the plot; Betty and Veronica are much more interesting to watch investigate the crimes that suddenly start flowering in Riverdale. Beaty says that the Archie comics are, essentially, efficient plot-generating machines, and in Riverdale the showrunners have discovered the perfect television counterpart in the soap opera.

When Riverdale first premiered, a common truism among viewers and critics seemed to have been that it was a CW take on Twin Peaks. The comparison is fair, as far as it goes. The problem is that it doesn’t say anything at all. The shadow of Twin Peaks stretches across the televisual landscape to such an extent that no show is untouched by it. Even The Sopranos shows Lynchian influence in its bizarre dream sequences. Even Mad Men, as a prestige soap opera, is walking in the footsteps of the prestige soap opera that was Twin Peaks. To say that Riverdale is a teen Twin Peaks is to say precisely nothing. But it’s a start in the right direction; the problem is that critics didn’t go far enough into the Lynch-Frost show’s DNA, to the original prestige television soap: Peyton Place.

Peyton Place (1964-1969) was more than a soap; it was an event. It was based on a 1957 movie, which was in turn based on a 1956 novel by Grace Metalious. It was an ambitious show; though many of Metalious’s rough edges were sanded off (gay characters are removed, the incestuous rape of Selena Cross—indeed, the very character—was removed, and so on), it still openly tackled issues like teen pregnancy. Showrunners even described the series as “a novel for television”. And, of course, it was responsible for introducing the world to Mia Farrow.

I mention Peyton Place because it is the fountainhead from which both Twin Peaks and Riverdale draw. Which is to say, they are part of a tradition. The American small town often functions as a way of meditating on contemporary issues. I could write a book on the topic. As Sinclair Lewis argues in the opening words of Main Street, “[t]his is America”—not just in the sense that Gopher Prairie is located in America but also because the issues facing Gopher Prairie are also the issues facing America itself.

And here, perhaps, I can make a bold assertion: for continuing this tradition, Riverdale is a better example of American small-town mythology than Twin Peaks. Make no mistake, Twin Peaks is a nearly-perfect series, and it condenses the central themes of American small-town fiction in important ways (incest, murder, disillusionment…). The movie Fire Walk with Me is undoubtedly the most thorough incarnation of American small-town mythology on the big screen. But Twin Peaks is also very distinctly the product of a pair of great artists working in tandem. Riverdale‘s aesthetic is distinct, but it is low-Postmodern: the show, both in terms of visuals and plot is, essentially, a collage of every cliché associated with small-town soaps, filtered through a neon-noir lens. Thus, Riverdale allows us as viewers to understand and appreciate the mythic dimensions of small-town fiction.

That’s helpful because it’s clarifying. Skeptics often claim that academics who study popular forms are diluting their discipline by putting, say, Micky Spillaine on the level of Shakespeare. But no one does that; Spillaine might be interesting, but he’s no Shakespeare, and everyone knows that. It’s a stupid accusation. No, what’s helpful about paying attention to “low” generic forms is that structures and tropes yield themselves readily to analysis. Twin Peaks is too idiosyncratic to tell us much about small-town fiction in the abstract; Riverdale, by its very generic nature, can tell us more.

And what it tells is that small-town fiction is obsessed with generational sins. Although shows like Peyton Place often focus on the adults as much as the children, the larger tradition — the novel Peyton Place or Kings Row by Henry Bellamann—are about realizing that the parents are not what they seem. Sherwood Anderson’s seminal Winesburg, Ohio (1919) is a series of vignettes by which the young George Willard comes to understand that the adults around him are leading desperate—and desperately lonely—lives. The small-town novel is above all things a bildungsroman. The young people of the town of Riverdale are on a journey to discover the secrets of their hometown, and this discovery plays out in large and small ways. On a personal level, each young lead discovers at some point that their parents are hiding something—past infidelities, abandoned children, murders…. The old, for their part, eat the young even (sometimes) in the process of trying to protect them.

Part of the way this cannibalism plays out is located in the theme of incest. Incest, which is central to small-town fictions from Kings Row to Twin Peaks, is sublimated in Riverdale. A running subtext in the first season of Riverdale is the idea that Cheryl and Jason Blossom are more than twins—that they are lovers. Ultimately, the show flinches away from this allegation; after all, if Cheryl is to be a long-running character, it is unwise to saddle her with a backstory as an incestuous twin. Nevertheless, the subtext is literalized when it is revealed that the Blossoms and the Coopers are related, so that when Betty’s sister was involved with Jason it was (not really, but close enough) incestuous. In season two, Betty’s father is revealed to be a serial killer who tempts Betty into a Hannibal Lector/Will Graham relationship—a relationship which, as portrayed in the Hannibal tv show, is highly sexualized. None of this is nearly as intense a form of incest as appears in other works; in Kings Row, Peyton Place, and Twin Peaks, incest takes the form of a father raping his daughter. Riverdale offers a diluted version of this theme—but it is still there. Something about the small town is predatory and is going to consume its young.

And that’s the key. Twin Peaks is a better show, but Riverdale is a more universal myth. As such, questions of quality are beside the point. Mythology does not require coherent scripting or marvelous acting, as any fan of Doctor Who could tell you. What it does require is simplicity. And here, again, is why Archie is so perfectly translated by the show. The figures we encounter in the pages of Archie comics are not three-dimensional figures. They are, in a real sense, mythic figures. Their arguments and adventures leave no mark beyond a single issue; they are as invincible as stone, as malleable as silly putty. They can meet KISS or The Punisher. They can even be evangelical Christians for a while. It makes perfect sense, then, for Riverdale to have them enact the primal mythic stories of the American small town.

The small-town myth is a tricky one. On the surface, it seems that celebrations of the small town are simple nostalgia; we long (presumably) for a simpler time, a more innocent age. We like to think of the small-town as a place of escape; talk about small-town values is a cliché that both the Democrats and the Republicans indulge in. Ideologically, as Ryan Poll observes, the small town narrative exists to cover the march of Empire westward. And so we go home—to Mitford, to Lake Woebegone, to Odyssey, to escape the harshness of the modern world. We look for a place of belonging, a community.

Or so it would seem. But the American small-town myth is more complicated than that.. It is a place where national anxieties are worked out. For the small town is never simply itself; this disillusionment with parents—with Riverdale itself—is part of a larger meditation on national sins. So it has ever been, all the way back to the Revolt from the Village of 1915-1930. As a result of its purity, Riverdale is able to meditate on contemporary anxieties. The #metoo movement is an important part of the plotline of season 2, as is gay conversion therapy. One episode features Jughead discovering that the origin-myth of Riverdale is a lie; the town’s founder was a bloodthirsty monster who destroyed the tribe who previously occupied the land. Surely this is simply a re-play of the debates that circulate every Columbus day?

And this, after all, is the real work of small-town fiction. Not so much to occlude national sins as to expose them in mythic form—to force them into awareness so that they can be grappled with and (maybe) exorcised. Riverdale isn’t the only narrative to do this. I’ve mentioned several already, but you could add more: Stephen King’s ‘Salems Lot and It, Thomas Tryon’s The Other, Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives…. All of these narratives (and many more) try to grapple with the unacknowledged, obscene core of the American experience—that the United States was founded on genocide and continues to insist on its own innocence while self-righteously tear-gassing toddlers. There is a darkness at the heart of the small town, as there is of America itself. There are monsters there.

In a way, this is what makes Riverdale so perfect, so compulsively watchable, and so subtly unsettling. The candy coating hides a bitter core. But to put it that way also makes Riverdale sound unbearably self-serious. It makes it sound like watching the show should be an exercise in Cultural Criticism. But this is a show in which the town’s economy revolves around maple syrup and a drug called—no kidding—jingle-jangle. It’s a show that centers a whole episode on a production of Carrie: The Musical (producer Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa wrote the screenplay for the 2013 Carrie reboot, so he’s got the bone fides). This is a show whose pleasures are not at all intellectual. They’re visual—the neon-noir cinematography, the beautiful twenty-somethings playing teens. They’re metatextual—the parents are all played by familiar faces from older teen soaps (including Mädchen Amick, who is—impossibly!—even better here than she was in the original run of Twin Peaks). This is not a show that’s designed to be subjected to heavy critique or analysis. And yet, in the middle of all this camp—at the core of a show that is not only trashy but gleefully trashy—there’s the beating, raw heart of American mythology.