Arrow Video’s release earlier this year of their new restoration of Robert Altman’s Images gives a wider audience a chance to reevaluate a film that seems to have been buried over the decades. Poor initial distribution, especially in the US, and mixed critical reviews combined to stifle the reception of this remarkable effort that occurs in the middle of Altman’s celebrated decade of the 1970s. He made Images in Ireland with backing of a British production company after his huge hit MASH, the bizarrely inventive Brewster McCloud, and the celebrated McCabe and Mrs. Miller, but before he returned to the US to create a quartet of films in 1973-75 that culminated in the epic Nashville. It is inevitable with a director with as long, varied, and prolific a career as Altman that some films will be better than others, and that some would find an audience while others would not. But it isn’t always the case that the quality and the popularity of a movie are perfectly correlated, and Images is a case where this is out of joint.

Images is the story of a woman who is going mad—more precisely, she is experiencing a type of schizophrenia that leads her to see and hear people and voices that aren’t really there. The woman, Cathryn (Susannah York), is writing a children’s story called In Search of Unicorns, which we hear portions of in voice-over narration throughout the film as she meditates on the story, or perhaps is composing it in her mind. She is writing at home alone when her work is interrupted by a phone call from her friend. The first intimation of a break in literal reality comes when there is an apparent crossed line on the phone, and a new voice on the phone interrupts her conversation to warn Cathryn that her husband is at that moment meeting another woman. If the line was crossed by chance, then how would the voice on the other end have been able to tell Cathryn this intimate information? Before we can find a resolution to this mystery, a more startling one is presented. When her husband Hugh (René Auberjonois) returns, he assures her that the phone message was untrue. But just as he moves to embrace Cathryn to provide her comfort, she sees a different man in his place, and leaps up from her bed screaming in fright.

Altman has said that this idea of suddenly seeing another man in the place of her husband was the genesis of the story of Images. The idea had first occurred to him some years earlier, but it was only when he assembled his cast, especially Susannah York, that the final shape of the film’s story and presentation came together. The rest of the story follows Cathryn and Hugh’s journey to a country home, where they are met by a friend and one-time lover of Cathryn’s, Marcel (Hugh Millais) and his young daughter, Susannah (Cathryn Harrison). The rest of the film primarily takes place in and around the country house, as Cathryn’s picture of reality fractures further and further. She continues to see the presence of her husband, the real and imagined presence of Marcel, and the imagined presence of the man who she had seen in her first frightening vision. This man is revealed to be another former lover, a man named Rene (Marcel Bozzuffi), who had died some years earlier. Compounding Cathryn’s and the film audience’s disorientation is the appearance of a doppelganger of Cathryn herself, and the fact that the young girl Susannah looks and tries to act like a younger version of Cathryn.

Altman made no secret that this tale of doubles and dubious reality was inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 film Persona. The influence of the Bergman film is evident, as are echoes of films like Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Psycho. There are premonitions of things to come later in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks or Mulholland Drive. But despite exploring similar thematic territory and mood to these works, the themes are filtered through Robert Altman’s distinctive vision.

The score by John Williams blends seamlessly with Altman’s meticulously layered sound design. Williams is perhaps best known for sweeping lyrical melodies and grand operatic textures, but in Images, he showed that he is also a master of the purely atmospheric score. Credit is also due to percussionist Stomu Yamash’ta for his contributions to the score as well. At his own request, Yamash’ta was credited for “Sounds” in the film. (For more on this extraordinary collaboration, refer to this article.) In an interview Altman says he had Williams’s score framed, and discussed the way that Williams had written descriptions of the sounds that he wanted Yamash’ta to create at particular points.

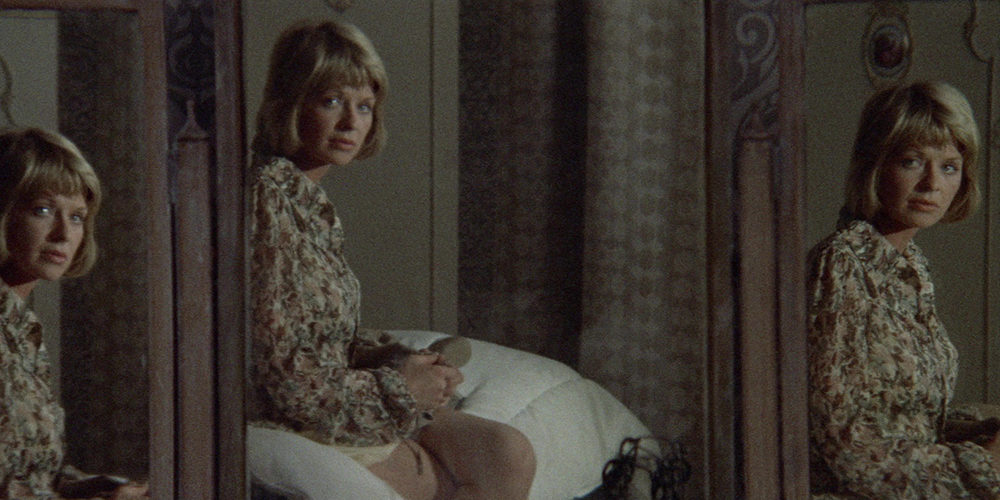

Of his films that I’ve seen, this is Altman’s most evocative use of landscape. The beauty of the open exteriors provides a sharp contrast to the cluttered, clutching interiors that reflect the tension of the narrative. Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond captures not only the beauty of the Irish hills and waterfalls, but also the evocative sets—from the cluttered and modern apartment that opens and closes the film, to the important car interior and the spare but symbol-fraught country home. He specializes in a sort of gauzy, glowing image that seems rarely employed in contemporary cinematography, but in this film is used with judicious but striking effect. Altman has said that he is “always attracted to reflections and images through glass, anything that destroys the actual image and puts different layers of reality on it.”¹ In Images, this includes mirrors (particularly multiple mirrors at once), the haze of fog or mist, rain on windows, and even just the varied use of the camera’s focal length to blur out important parts of the image. There’s also a rich use of matched cuts or dissolves from scene to scene, such as from a pool of blood to the red reflections of the sun rippling on a pond, or from the twin lenses of a stereopticon to a pair of rounded mirrors on the headboard of a bed, or finally from the stream of a shower to the cascade of a waterfall.

The film is overloaded with visual and verbal symbolism related to Cathryn’s journey into a more and more fragmentary and confused perception of her situation. The prominent motif of the jigsaw puzzle that several characters work on brings together this notion of fragmentation with another important symbol which Susannah York herself infused into the story. Under the closing credits, we see someone place a piece in the nearly-completed puzzle, which is revealed to be an image of the country house and its surroundings. The last piece placed is the head of a unicorn in the forest. The character Cathryn’s book, In Search of Unicorns, is also revealed to be a real story written by Susannah York. This crossing of the lines between actor and character undoubtedly is a result of the highly collaborative, improvisatory nature of Altman’s filmmaking approach. It is further indicated by the fact that the characters all share the names of the actual actors, but in mixed up ways, so that Cathryn Harrison plays Susannah, Susannah York plays Cathryn, and so on.

This may seem a little meta-textual, and outside the scope of a strict analysis of what the film is and does, but I think that Altman wants us to consider this film on that level. Cathryn’s character breaks the fourth wall and looks directly in the camera on multiple occasions throughout the film, as if to remind us that we, the audience, are participating in the construction of the reality of the narrative through our viewing. The frequent appearance of cameras throughout the film (Hugh is an amateur photographer) seem to be another way of looking back at us as well, since so often when we see them we are looking straight into the lens. Unlike Persona or David Lynch’s work, this film leaves little narrative ambiguity, and ultimately comes together a little too neatly, like the puzzle that is under the closing titles. Ultimately, I think the film might’ve been strengthened by a more ambiguous resolution, given the way that it constantly reorients our perception alternately by shocks and more subtle clues. I don’t think the thriller and horror aspects are as important as other themes, however, but the film still succeeds as a genre film through the constant increase of tension that is masterfully balanced. Images is a masterpiece of suspense, which shows that if Altman had wanted to make a career as the heir to Hitchcock, I think he could have done so. It seems to me that the neatness of the plot’s resolution, where it becomes clear to the audience exactly what is real and what is imaginary, is one of the ways in which Altman shows a debt to the storytelling of Hitchcock’s thrillers.

On a thematic level, despite the fact that the central character is mentally ill, the film is also exploring things that are universally experienced. The depiction of Cathryn’s struggles with the three men in the story is a brutal, yet recognizable evocation of the way that all our past memories are both a part of us, yet in some way represent distinct, other people than our present selves. Many of us feel at least on some level the desire to put the past behind us, even “kill” it. Cathryn’s conflict also enacts the complicated ways that guilt and past relationships intersect with present ones.

Cathyrn’s, or more properly, Susannah York’s story about unicorns also might give insight into the film’s themes. Unicorns today are perhaps seen as a mythic, magical creature of fantasy that appeals mostly to young girls, but which may be fairly neutral in terms of symbolism. Traditionally, however, the unicorn was representative of youth, and perhaps virility, as in Gian Carlo Menotti’s musical fable, The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore. Going back to medieval times, the unicorn was considered “too strong for any hunter to take; but if you set a virgin before him he loses all his ferocity, lays down his head in her lap, and sleeps. Then we can kill him.” (C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image.) This mythic image was at some point interpreted as a Christian allegory of Christ, but other, perhaps more Freudian symbolism might be apparent as well. The way in which Susannah York reads her story on the soundtrack of the film lends it a more impressionistic quality that makes it hard to pin down the story itself from the fragments, or even to assign any definitive symbolic interpretation. It seems fair however, to to suggest that the unicorns are at least a symbol of childhood innocence, and if considering a medieval Christian allegory seems to strain too far, at least we can see a longing for a sort of redemption in the sense of a return to simplicity, youth, and wholeness.

The unicorn symbolism is as tangled as anything else in the narrative, however. If that wasn’t apparent, we are given another visual example in the still life of the antelope’s head that Hugh has arranged on the kitchen table for a photograph. Altman gives us a side view of the tableau, with Cathryn standing up on a chair to peer through the camera down at the animal’s head. From the side, the animal seems to have a single horn—a unicorn. But when we view the tableau from Cathryn’s point of view, which is also the camera’s point of view, we look straight into the dead animal’s face, and of course the single horn is shown to be in reality two. In such ways, Altman deftly layers symbolism into the plot, all the while attempting to bring us out of the world of the narrative and back into it, through a splitting and re-joining of the character and the actor-creator in our own perception.

¹ From Altman on Altman, reprinted in the Arrow Video Blu-ray booklet.