There’s no question of Johnson’s relevance. For decades, artists like Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Bruce Cockburn, and Ry Cooder—and, on a recent compilation, Tom Waits, Lucinda Williams, and the Cowboy Junkies—have been peeling back Johnson’s rough outer layer and exposing hidden treasures. Heck, there’s a Johnson track on the famous “gold record” aboard both of the Voyager spacecraft—he may yet become the first Earthbound recording artist to make the charts in another galaxy. No matter how many covers I hear, though, I still find myself drawn to the originals in an attempt to mine their depths for myself. It’s never easy going, but it’s worth it. Despite his theological naïveté, simplistic lyrics (often barely decipherable), and belt sander of a voice, there’s something ineffable about Johnson, something that shines in a way he probably wasn’t even aware of. And there’s something else—or perhaps it’s the same thing—that gets under my skin, that haunts me around every corner.

Johnson, it turns out, is even relevant to the COVID-19 outbreak. It’s fashionable to talk about whose advice could have helped the president avert the present crisis. He should have listened to the CDC. Or the WHO. Or Secretary Azar. Or Dr. Fauci. Or Tony Navarro. But really, they all should have listened to Blind Willie Johnson. It’s all there in his song “Jesus Is Coming Soon,” which is only tangentially about Jesus and really about the 1918 influenza pandemic. The “mighty disease,” in Johnson’s telling, travels through the air, afflicting civilians and military alike “on the land and on the sea.” It closes schools and churches. And doctors for a time are confused about what to call it. Johnson reminds the listener: “We done told, our God done warned you.” He could be talking to the president. He’s certainly talking to you and me.

This isn’t the first time in recent years that a Blind Willie Johnson song has proved eerily prophetic. It’s tempting to say that a song takes on new meaning, but perhaps it’s more accurate to say that circumstances reveal layers of meaning which were always there but I hadn’t considered before.

In the previous case, the song was “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger Right,” which I’d first learned circa 2011 because I was putting together a blues set for a Christmas gig and it’s the only Blind Willie song that has anything to do with Christmas: “Well, Christ come down as a stranger / He didn’t have no home / He was cradled in a manger / And the oxen kept him warm.” I thought of it as a simple gospel song about hospitality, and performed it several times as such.

But then.

In early July 2018, just as the bottomless cruelty of the present administration’s immigration policy fully seized the public’s attention, and phrases like “kids in cages” and “family separation” entered the national dialogue, my church’s worship leader asked me to perform an offertory—you know, the music that plays while the ushers pass the plates. After some contemplation, the idea of singing “Stranger” entered my head. And just like that, the simple gospel song became a fiery protest anthem. I was fortunate that Sunday to be paired with Ben, the church’s best roots/gospel pianist, and one of my backup singers was a young man from the Democratic Republic of the Congo named Providence (really, that’s his name) who’s an incredible gospel vocalist in his own right. So we put together a musically scorching take on “Stranger,” complete with a real live immigrant—but the lyrics! They scorch all on their own. Blind Willie couldn’t have known he was reprimanding powerful white men yet to be born when he wrote the song. Still, reprimand them he did:

Be careful how you treat a stranger

Be mindful how you turn him away

You may be entertaining an angel

Would you drive him from your gate?

Everybody ought to treat a stranger right

Long way from home…

All of us down here are strangers

This world is not our home

So don’t you never hurt your brother

And cause him to stumble on

Johnson recorded “Stranger” at his final recording session, in Atlanta on April 20, 1930. It’s impossible to say what was on his mind. But surely he knew that things had taken a turn for the worse, that people who had lost their jobs would need the compassion he was singing about, that this would be no time to turn strangers away. The Depression took its toll on Johnson’s recording career as well: sales were slow, and only 800 copies of “Stranger” were pressed.

Additional levels of irony arise when one considers the circumstances of Johnson’s death. In his later years he had settled in Beaumont, Texas, near the Louisiana border—a musically fecund region that produced legends like roots/blues guitar hero Clarence Gatemouth Brown and Western swing mandolin picker Tiny Moore, among others. A fire gutted Johnson’s house in August 1945, but having nowhere else to go, he and his second wife, Angeline, continued to live in the burned-out ruin, which failed to adequately shield them from the elements. This led to a fatal case of what his death certificate called “malarial fever.” Angeline later claimed that the local hospital had refused to admit Johnson—either because he was blind or because he was black. So, the blues preacher who warned us against turning away strangers? He died at 48, a stranger after being turned away.

To backtrack a little, the session that produced “Jesus Is Coming Soon” took place in Dallas on Dec. 5, 1928, and was supervised by talent scout Frank B. Walker of Columbia Records. Johnson’s first wife, Willie B. Harris, was with him in the studio. Also recording that day with Walker was Washington Phillips, another Texas blues gospel singer who in some ways was Johnson’s polar opposite—where Johnson’s voice is low and guttural, Phillips’s tenor is plaintive and prim; where Johnson’s guitar playing is sinewy and primeval, Phillips plucks away cheerfully at a homemade instrument called a “manzarene” that he fashioned from two fretless zithers, evoking a roomful of cherubs busy with their harps.

Both men had made their debut recordings with Walker a year earlier, in December 1927, that time a couple of days apart rather than on the same day. For Johnson, this first session earned him more than three hundred dollars and yielded six songs, including “Dark Was the Night (Cold Was the Ground),” the spectral, wordless slide guitar masterpiece that became his best-known record and now has slipped the surly bonds not only of earth but of the entire solar system. Amanda Petrusich writes in The New Yorker:

Johnson plays his acoustic guitar with a bottleneck slide—or maybe a penknife—and moans a great deal. His singing voice is raw and gory, like the sound of something alive being slowly fed into a meat grinder. The song has no lyrics; Johnson seems given over, only half there. “Mmmm-mmm, well, oh well,” he mumbles. There is an indescribable depth of melancholy in his vocal. I can’t imagine what Walker must have been feeling, hearing Johnson and Phillips perform in the same weekend—the sorts of dreams he must’ve had, what he saw at night when he closed his eyes.[1]

Whatever Walker felt, it didn’t stop him from bringing Johnson and Phillips back to Dallas the following year for more sessions. We also can only guess at what Johnson was feeling, or why he and Harris chose that day to record a song whose verses recount an influenza pandemic that had concluded its deadly course eight years prior, and whose chorus associates that pandemic with a dire warning about the second coming of Jesus. (It’s the first topical song Johnson recorded, and one of only three—another, “God Moves on the Water,” is equally frightening in that it ascribes the sinking of the Titanic to God’s wrath.)

Columbia’s interest in Johnson is easily understood: his records were hits. His first 78 saw total pressings of 15,400 copies—more than the latest disc by Bessie Smith, an established star—and the next two yielded 6,675 copies each, well above average. In fact, on the same day he recorded “Jesus Is Coming Soon,” he also made a pair of sides under a pseudonym, Blind Texas Marlin. It’s believed that these were secular songs that Walker intended to release to propel the artist to further stardom, broadening his appeal beyond gospel music—but no titles were recorded for the songs, no pressings were made, and the master has been lost.

For Johnson’s part, the three hundred from his first session—nearly $4,500 in 2020 dollars—was quite likely the largest amount of money he’d ever put his hands on. For an unspecified bonus, he had signed over his royalties, so record sales wouldn’t have mattered to him, but surely he wanted to bring material to the session that was strong enough to keep his new career going.

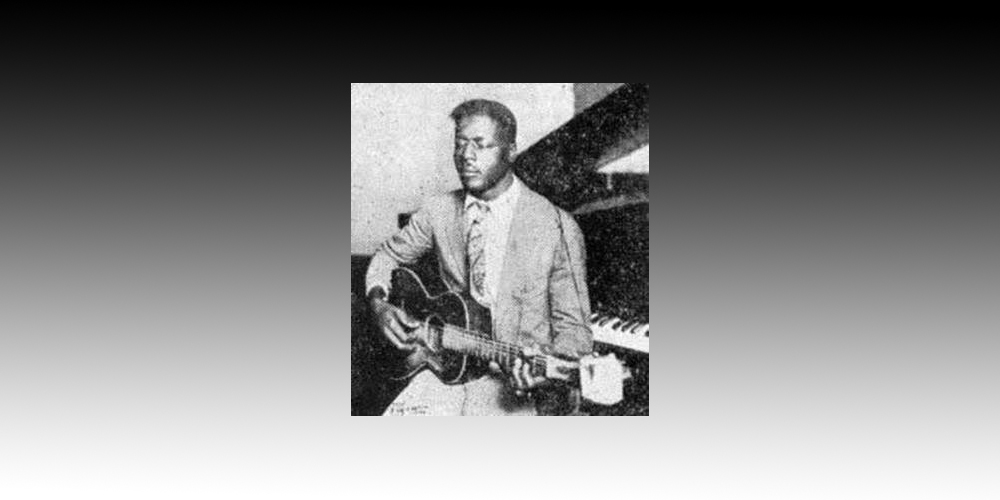

Recording success notwithstanding, Johnson was still a street singer. The publicity photo that Columbia used to market his records—the only known photo of him—clearly shows a tin cup attached to the headstock of his guitar. The songs he brought to record with Walker had been honed in that most unforgiving of performance settings, and he knew which ones put money in the cup. So there’s no reason to think he and Harris had any doubts whatever about “Jesus Is Coming Soon.” Furthermore, the song is quite plainly all about the lyrics, because that’s pretty much all there is to it. There are no slide guitar breaks, none of the rare moments when the singer relaxes his larynx and slips into his natural baritone. Johnson doesn’t even change chords—just fingerpicks away steadily in open D tuning, with the capo on the fifth fret, while he declaims the verses and Harris joins him for the choruses.

That Johnson is treating the influenza pandemic as an act of divine judgment is clear from the opening line: “In the year of nineteen and eighteen / God sent a mighty disease.” The following verses tell a straightforward narrative of how the virus spread and how people reacted to it, but the chorus snaps the listener back to the sermon: “We done told, our God done warned you / Jesus coming soon.” Finally, verse 5 starts drawing conclusions: “Well, God is warning the nations / He’s warning them every way / To turn away from the evil / And seek the Lord and pray.” So does that mean the pandemic, in Johnson’s view, was a judgment or just a warning? Well, it means both. After a sixth verse about closing public schools and churches, Johnson pitches his sharpest rebuke yet: “Read the Book of Zechariah / Bible plainly say / Thousands of people, they did die / On account of their wicked ways.” And just like that, the song is over, with a crisp guitar strum for punctuation. No final chorus to soften the blow.

There’s no getting around it: I know the connections Johnson is making were common in American religion at the time, and can still be found today among the likes of Pat Robertson—but I disagree with them. I don’t like Johnson’s theology here, and of course I think I have the better argument—based, naturally, on the teachings of Jesus:

There were present at that season some that told him of the Galileans, whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. And Jesus answering said unto them, Suppose ye that these Galileans were sinners above all the Galileans, because they suffered such things? I tell you, Nay: but, except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish. Or those eighteen, upon whom the tower in Siloam fell, and slew them, think ye that they were sinners above all men that dwelt in Jerusalem? I tell you, Nay: but, except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish.[2]

It’s foolish to claim that this or that calamity is a judgment against the wicked when Jesus himself scoffed at the very idea (although Jesus was willing to cite such events in a general call to repentance). But people still manage to do it, and Blind Willie Johnson was one of those people. Does that mean we can ignore the song? Perhaps others can, but I cannot; rather, it means that once again I’ll have to look for other layers of meaning.

The first version of this song that I heard wasn’t Johnson’s. It was a reworked version by Glenn Kaiser and Darrell Mansfield, on their 1990 disc Trimmed & Burnin’, a tribute to Johnson and the Reverend Gary Davis. Mansfield takes the lead vocal, throws out most of the verses about the pandemic, and substitutes this one:

People dyin’ of starvation

People dyin’ of AIDS

People killin’ their babies

Cryin’ save the whales today

There are two ways to interpret that: the first, which is nothing short of horrific, would be to suggest that he’s saying starvation, AIDS, and abortion are all manifestations of God’s judgment for wickedness. The second, which is more palatable, would be that he’s imploring Christians to get more involved in the world to alleviate suffering. This latter reading is supported by the way Mansfield subtly changes the chorus: “We been told, our God has warned us / Jesus comin’ soon.” In Mansfield’s version, believers aren’t so much doing the warning as being warned themselves, along with everyone else; Jesus is coming for those who count themselves righteous as well as for the wicked. That brings the chorus more in line with Jesus’ remark about the tower in Siloam, but Johnson’s most problematic verses (the first and last ones) remain. Mansfield hasn’t really resolved the central difficulty, just updated it.

And what of Zechariah, the Old Testament prophet whose name Johnson flings at us to conclude the song? It’s relatively easy to cherrypick a dire warning from almost any minor prophet, but Zechariah is mostly an upbeat book whose oracles chiefly concern the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem. The best-known use of a Zechariah text just might be “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion” from Handel’s Messiah—the very opposite of direness, surely.

Zechariah does take a few digs at the enemies of Jerusalem, promising that they’ll get theirs eventually. However, if we’re looking for the verses that Johnson might have had in mind, nothing in the book lines up exactly—but the closest might be this:

Be ye not as your fathers, unto whom the former prophets have cried, saying, Thus saith the Lord of hosts; Turn ye now from your evil ways, and from your evil doings: but they did not hear, nor hearken unto me, saith the Lord. Your fathers, where are they? and the prophets, do they live for ever?[3]

Writing in 520 BC, when the Babylonian exile was over and the rebuilding of Jerusalem was already underway, Zechariah implores his audience not to be like previous generations of Judeans, whose “evil ways” he blames for their captivity in Babylon 70 years earlier. Johnson notwithstanding, Zechariah doesn’t “plainly say” that those Judeans died “on account of their wicked ways.” It’s more subtle than that. “Your fathers, where are they?” he writes, dropping a strong hint—but then he goes on to note that the prophets who warned those fathers are dead as well. Except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish.

It’s tempting to assume that Johnson wrote “Jesus Is Coming Soon” around 1920, not long after the events it describes, but available evidence suggests otherwise. His other two topical songs, “When the War Was On” and “God Moves on the Water,” recorded in December 1929 in New Orleans, both draw from a 1927 Paramount 78 by William and Versey Smith, another gospel blues duo. So too, perhaps, with “Jesus Is Coming Soon”—rather than occupying his repertoire for eight years, it could well have been assembled by Johnson a few months before he recorded it, from bits of folklore that had occupied the ether ever since the days of the pandemic. The events he sang about weren’t fresh; things were going well for both Johnson and the nation, so why invoke apocalypses past and future? Apart from putting money in the tin cup, who can say?

Johnson wasn’t, of course, the first writer to treat the events of 1918 as a harbinger of the end times. I can’t help but think of William Butler Yeats’s “The Second Coming,” which he began writing in January 1919, in the wake not only of the Great War but of the Easter Rising, the Bolshevik Revolution, and who knows, perhaps the flu pandemic as well:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

This has little in common with Johnson’s approach; rather than treating recent events as a fulfillment of Christian belief, Yeats, who had been kicked out of the London Theological Society, sees in them a collapse of everything Christendom formerly held sacred. If Yeats ever heard Johnson’s song, he might well have tagged the singer as having too much in common with “the worst” who “are full of passionate intensity.” In Yeats’s telling, things are so messed up that what’s coming soon is not Jesus at all, but a “rough beast” that “slouches towards Bethlehem”—“A shape with lion body and the head of a man, / A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun.”

Though I strive to be more of an optimist than Yeats, I still lament the thorough devolution of evangelical Protestantism from early Christianity. Jesus himself asked, “Nevertheless when the Son of man cometh, shall he find faith on the earth?”[4] What if that wasn’t a rhetorical question? If Jesus came back and saw what’s going on in his name, not only might he “never stop throwing up,” to quote Max von Sydow in Hannah and Her Sisters, there’s also a chance he might abandon the whole project and leave Bethlehem to the rough beast.

So what, if any, deeper meanings can be made plain here? If we reject the notion that a plague was sent to judge us for our wickedness, can we still regard it as a warning of some kind? Of course we can. At the end of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, you’ll recall, it’s microbes that vanquish the Martians. The unnamed protagonist peers into the invaders’ camp and finds them “slain, after all man’s devices had failed, by the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put upon this earth.” Has Mother Nature had enough of humankind’s ravages? Is this the beginning of her MeToo moment? Is she writing a new War of the Worlds in which the microbes win again, but this time by taking out humans? If so, it ain’t gonna be just science fiction. We done told, our God done warned you—or at least Pope Francis did:

There is an expression in Spanish: “God always forgives, we forgive sometimes, but nature never forgives.” We did not respond to the partial catastrophes. Who now speaks of the fires in Australia, or remembers that 18 months ago a boat could cross the North Pole because the glaciers had all melted? Who speaks now of the floods? I don’t know if these are the revenge of nature, but they are certainly nature’s responses.[5]

Twice in Genesis God instructs people to “replenish the earth.”[6] Whatever you call our present campaign of environmental destruction, it doesn’t look like replenishment. Nature’s responses may be just getting started. It’s easy to point fingers and blame China, where the new coronavirus appears to have crossed from horseshoe bats to humans, although the exact transmission route is yet unproven.[7] But the next pandemic may come from elsewhere—the Arctic permafrost, which is rapidly melting and releasing 30,000-year-old viruses and God knows what else, seems a likely candidate.[8]

Furthermore, the countries now topping the list of COVID-19 cases and fatalities are those, including mine, where governments failed to act quickly and decisively and/or citizens failed to heed warnings. On Friday, March 13—the day the president declared a national emergency—my wife and I celebrated our anniversary by staying in a downtown Seattle hotel and eating in its restaurant. Nursing home patients not half an hour’s drive from my house had been dying for two weeks. It was, I suppose, our little squeak of protest against the restrictions we knew were probably coming. But now, four weeks later, it seems incredibly risky and I’m glad we didn’t get sick. And yet people are still out there taking similar risks. Reportedly, casual attitudes toward social distancing prevail in places where people are also skeptical about climate change.[9] God is warning the nations, he’s warning them every way—but if this warning doesn’t work, what will he try next?

Finally, what of Washington Phillips, the gentle, sweet-voiced soul who also recorded for Columbia in Dallas on Dec. 5, 1928? He quite likely passed Johnson in the hallway or the waiting room after his own session, lugging his unwieldy manzarene. Perhaps he stopped for small talk; it’s almost certain the two men knew of each other, even if they didn’t know each other. The two sides Phillips recorded that Wednesday were Charles A. Tindley’s sentimental “What Are They Doing in Heaven Today?” and “Jesus Is My Friend.” The latter, fortunately, has naught to do with the infamous Sonseed song from the early ’80s; rather, it consists of Phillips speaking a couple of stanzas of doggerel he probably wrote himself before launching into an abbreviated version of “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” the familiar hymn by Joseph Scriven to a tune by Charles C. Converse. Older than Johnson by 17 years, Phillips had also had a good year in record sales, moving 8,725 copies of his debut 78, and doesn’t sound interested here in angry social commentary, preaching divine judgment, or upsetting any applecarts.

But when Phillips returned to Dallas a year later for his last session, five weeks after the stock market crash, things were different. He recorded a two-parter, “The World Is in a Bad Fix Everywhere.” No doubt Johnson would have approved of a title like that, but we don’t know if he ever heard the song: it was never pressed or released, and just like Johnson’s Blind Texas Marlin sides, the master remains lost to this day. Petrusich muses:

[A]nyone who is prone to chasing ghostly emanations understands the dizzying, treacherous allure of such a thing. Even the title feels teasing, as if it might contain information about how to right our perpetually wobbling ship. Though we now know more than ever about Phillips’s life and work, it’s difficult not to get swallowed up anew by the romanticism and possibility of it all, to wonder what remains, obscured. It is easy to believe that if anyone might know how to lead us kindly toward salvation it’d be Phillips, hugging his manzarene, singing softly of Heaven.[10]

Indeed, Phillips’s song may sound like the song we need right now. But Johnson’s “Jesus Is Coming Soon” is the song we have. We might as well listen.

[1] Amanda Petrusich, “Some of Us Are Haunted by Washington Phillips,” The New Yorker, Oct. 20, 2016. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/some-of-us-are-haunted-by-washington-phillips

[2] Luke 13:1–5 KJV

[3] Zech. 1:4–5 KJV

[4] Luke 18:8 KJV

[5] Austen Ivereigh, “Pope Francis says pandemic can be a ‘place of conversion,’” The Tablet, April 8, 2020. https://www.thetablet.co.uk/features/2/17845/pope-francis-says-pandemic-can-be-a-place-of-conversion-

[6] Gen. 1:28, 9:1 KJV

[7] Matt Ridley, “The Bats Behind the Pandemic,” The Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2020. http://www.rationaloptimist.com/blog/bats-behind-the-pandemic/

[8] Brian Resnick, “Melting permafrost in the Arctic is unlocking diseases and warping the landscape,” Vox, Nov. 15, 2019. https://www.vox.com/2017/9/6/16062174/permafrost-melting

[9] Patrick Sharkey, “The US has a collective action problem that’s larger than the coronavirus crisis,” Vox, April 10, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/10/21216216/coronavirus-social-distancing-texas-unacast-climate-change

[10] Petrusich, “Some of Us Are Haunted by Washington Phillips.”

Reading List

Allen, Woody. Hannah and Her Sisters. Orion Pictures, 1986.

Blakey, D. N. Revelation: Blind Willie Johnson the Biography. Self-published, 2016.

Ivereigh, Austen. “Pope Francis says pandemic can be a ‘place of conversion,’” The Tablet, April 8, 2020. https://www.thetablet.co.uk/features/2/17845/pope-francis-says-pandemic-can-be-a-place-of-conversion-

Johnson, Blind Willie. The Complete Blind Willie Johnson. Columbia Records, 1993.

Kaiser, Glenn and Darrell Mansfield. Trimmed & Burnin’. Grrr Records, 1990.

Petrusich, Amanda. “Some of Us Are Haunted by Washington Phillips.” The New Yorker, Oct. 20, 2016. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/some-of-us-are-haunted-by-washington-phillips

Phillips, Washington. Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams. Dust to Digital, 2016.

Resnick, Brian. “Melting permafrost in the Arctic is unlocking diseases and warping the landscape.” Vox, Nov. 15, 2019. https://www.vox.com/2017/9/6/16062174/permafrost-melting

Ridley, Matt. “The Bats Behind the Pandemic.” The Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2020. http://www.rationaloptimist.com/blog/bats-behind-the-pandemic/

Sharkey, Patrick. “The US has a collective action problem that’s larger than the coronavirus crisis.” Vox, April 10, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/10/21216216/coronavirus-social-distancing-texas-unacast-climate-change

Wells, H. G. The War of the Worlds. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/36

Wirz, Stefan. “Illustrated Washington Phillips Discography.” Wirz’ American Music. https://www.wirz.de/music/phillipsw.htm

Yeats, W. B. “The Second Coming.” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43290/the-second-coming