RUD: Where do the ideas for your novels start and how long does it take them to fully gestate?

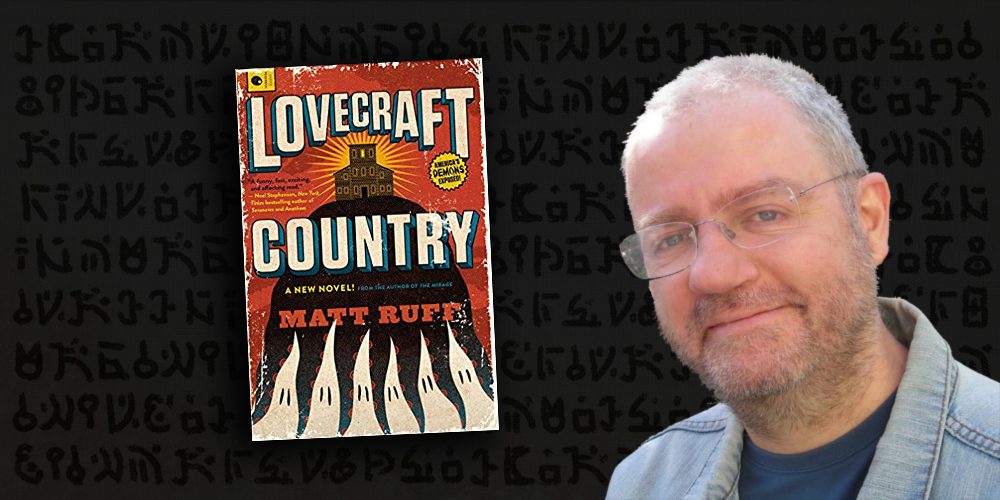

Ruff: The novel ideas come from all over the place. In one of the weirder instances, my second novel, I started out with just a weird idea for a title. I was procrastinating and trying to come up with the weirdest title for a trilogy that could still work and that eventually evolved into a satire of Ayn Rand. In this case with Lovecraft Country, I was working on ideas for a TV series pitch back in what must have been 2007 or 2006. One of the things I wanted to try my hand at was an X-Files-type story where you would have a recurring group of characters having weekly paranormal adventures and doing something that would allow for a different group of characters and set of social issues than you get in the more typical versions of that show format.

I hit on this idea of setting it in the 1950s and having my characters be a black family living in Chicago who owned a travel agency and published a guide for black travelers in the United States. It was partly inspired by reading a great book by James W. Loewen called Sundown Towns about the secret history of whites-only communities in America. In passing he mentioned that there were real guidebooks like what I call The Safe Negro Travel Guide in the novel. The most famous of these was The Negro Motorist Green Book, and as soon as I heard about that, I thought it would be really interesting to have a story where my Fox Mulder character was a field researcher for one of these guides, whose job it is to drive around looking for hotels and restaurants that will take him in. At the same time, he has both paranormal adventures and more mundane encounters with Jim Crow America. I couldn’t convince the television folks ten years ago that was a great idea, so I spent five years figuring out how to make it work as a novel.

A long gestation period isn’t unusual. At any given time, I’ve got half a dozen half-baked novel ideas bouncing around in my head, and it can take anywhere from a few years to a couple decades for one to come to fruition. In this case, there were probably some thoughts that went all the way back to college, but the real start was with the discovery of The Green Book. It took about 5 years of really hard thought to get started and another 3-4 years to write.

RUD: What was the novel or short story you read first that made you want to become a writer? Which authors did you or do you look up to?

Ruff: You know, I don’t actually know where the initial impulse came from. Basically, I’ve always loved making up stories. I mean if it came from anywhere it probably came from my mom. She was a missionary’s daughter who grew up in Brazil and Argentina–in the jungle–and so my mom was always great for wild stories. I probably got my love of storytelling from her and my grandfather before her. I say that I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was 5 years old, but that’s really just because that’s about as far back as I can remember anything. I’ve always wanted to do this. It wasn’t one specific story that made me want to do it. This is what I do and I found out that you could actually get paid for doing it.

RUD: Cory Doctorow mentioned in his review of Lovecraft Country that you were inspired in part by Pam Noles’ 2006 essay, “Shame.” How did her essay play into the process of writing the novel and what other influences were key to the process for you?

Ruff: “Shame” is about the difficulties and heartbreak of being a black science fiction fan. Noles was not the first black person I’d heard express displeasure about that. It’s an old story, but there was something about that essay that really crystallized things for me, I think because she talks first about her being too young to get it herself. Her parents basically try to clue her into the fact that she loves a genre that doesn’t love her back. Then her impression of going to see Star Wars–which if you’re my age is this religious experience all kids had in early adolescence–she enjoyed it as much as I did, but, at the same time, Star Wars was the moment when she finally realized what her parents were telling her. This entire universe was basically all white people with the exception of an X-wing pilot who gets blown up over the Death Star. That just sort of clicked for me and really sunk home and made me think about this being something I could incorporate into the story. I came upon it at just the right time.

I was thinking about ideas that would ultimately become Lovecraft Country and again that became part of the novel. My main character Atticus and his Uncle George who runs the travel agency are both black nerds in the 1950s and both have this same problem but multiplied even more so back then. They love this genre that doesn’t really make room for them, that at best ignores them and at worst insults them as the price of admittance. I just thought that would be really interesting to build a story around and then give these characters a chance to be the protagonists of their own real-life versions of the stories they love. So, I think Pam Noles’ essay and Sundown Towns were two of the biggest written influences I’d say for getting me going. And, of course, The X-Files and other shows like that which I grew up with. And my own nerdery in general.

RUD: I went into reading Lovecraft Country with some trepidation knowing the ease of translating black narratives through the white imagination, or “white gaze.” Was that a significant concern for you as you were writing and did the process of writing a book that places a dignified and fully characterized black family at its center challenge you as a white author?

Ruff: It’s funny, when I would talk to people about what I was doing, there was a lot of concern expressed by, particularly, my white friends. They would say “oh geez, I don’t know if you’ll be able to pull that off.” But part of what I love about writing is telling stories about people from different backgrounds than me who have different worldviews than I do. I’m not trying to say it wasn’t difficult at points, but I didn’t find it unusually challenging or difficult. It’s just my thing, putting myself in the head of someone else and trying to construct a psychologically realistic portrait of them. Keeping my own way of looking at things separate from their way of looking at things and just telling what I hope is a good story.

I think for a lot of white authors in particular, they are just not really interested, whether they admit it or not, in telling stories about black folks or other folks who aren’t them. Or they’re doing it because they feel like they have to and don’t want to get in trouble for not being diverse enough. But it wasn’t a chore for me. If you address it like a chore then it will read like a chore and it’s not going to be very interesting. If you’re having fun then it’s a good kind of difficult, I guess is the way I would describe it.

I approach the characters as individuals. I don’t want them to just be types, I want Atticus to be distinct from George to be distinct from Hippolyta to be distinct from Ruby and Letitia. If they were all the same character with slightly different faces, that would just bore me to tears really quickly.

I have the advantage of practice too. I’m an old guy now and I’ve been doing this for a long time. I’m 30 years in. I’ve gotten all of the flatter characterizations out of the way some time ago.

RUD: It’s stunning how well your book undercuts the racism of H.P. Lovecraft simply by reversing Lovecraft’s formula: those he considered to be subhuman were the heroes, were the “normal” people in the book, they were given full dignity whereas the antagonists–whether they were the main villain or bit players–were white. What went into making that decision as a writer?

Ruff: I did make a command decision early on in the process to make all of viewpoint characters African American. I wanted to stick with them and their view of racism and what they had to put up with. This did create some logistical challenges as far as communicating what the white characters were up to when they were off alone together. But I thought that would be a better way to stay focused on racism as an existential threat rather than being distracted by white concern about being implicated in racism. Another place where white authors sometimes go astray is they really want to make sure that everybody understands that they think this is bad stuff. But a black man getting pulled over by the cops isn’t concerned about the state of your soul, he’s worried about whether he’s gonna get shot. And that’s what I wanted my story to be about.

What’s fascinating about Lovecraft’s fiction is he had a very specific set of fears and dreads, but he also tapped into this more universal sense of fear of people who are different from us, who have no mercy for us. So you can take a lot of his story ideas and plug in a black protagonist, and it actually still works. They’ve just got somewhat different people coming after them. The fear is more realistically grounded in the kinds of hate crimes that actually occur in the world. If you’re white, you don’t generally have to worry about stopping in the wrong town overnight and getting killed by the populace. If you’re black, you really do, even today. I wanted to take what worked in Lovecraft and do it with a black protagonist and wring some changes on that idea. The initial idea was more X-Files than Cthulhu, but once I realized that the book was about contrasting these paranormal horrors with the mundane horrors of racism, I needed a dramatic bridge between the two. Lovecraft was kind of perfect for that, because he’s both cosmic horror and white supremacy. So that’s where the title came from.

RUD: As someone who clearly respects the writing of H.P. Lovecraft, but detests his racism, what wisdom would you give to readers about partaking in the creative output of Lovecraft without giving assent to the beliefs of the man in the process?

Ruff: I mean this comes up a lot now in discussions online, but personally I just don’t worry about it much. I grew up in a conservative Christian household in the 1970s, so I long ago worked through this fear of being corrupted by popular culture. When I was a kid, there was all this talk about Dungeons & Dragons being the devil’s game, and how playing it would turn you into a Satanist, and of course that was ridiculous. And I found as I grew older that even stuff I genuinely regard as vile is not going to corrupt me unless I want it to. I tell the truth about what it is, but I don’t need to worry about it turning me into something.

The real problem I have with racist literature is not that it’s gonna make me a bad person, it’s that the narrow-minded worldview that creates it is generally just not very interesting. Lovecraft is an exception, which I think is why we still read him, 80 years after his death. He’s got a lot going on there that transcends his own limited worldview. I find his racism more annoying than anything else. “Stop embarrassing yourself and focus on the parts of this that work! There’s more here than even you realize.” But he’s dead, so he’s not going to hear me.

Anyway, I don’t think you have to worry about it–or if you are worried about it, you should be less worried about what it’s going to do to you than worried it’s going to expose feelings you already have, that you don’t want to admit to.

RUD: One of the most compelling parts of Lovecraft Country is how many chapters are opened with an historical quote from primary sources like the Safe Negro Travel Guide or the Chicago Real Estate Board or even eyewitness testimony from the Tulsa Race Riots of 1921 and then how those elements are placed into the realistic terror of each chapter specifically. Did you set out to address specific aspects of racism in society in each chapter? Or did the narrative drive those stories to those places naturally?

Ruff: It was really a little of both. There were things I would read about in my research that I thought would be interesting to incorporate. The classic example probably being Letitia coming into a surprise windfall and deciding to buy a house in a white neighborhood and it turns out to be haunted. That sort of encapsulates taking a story form that’s been done to death—first-time home buyer gets a deal that’s too good to be true and it’s because there is a ghost—and doing something with it that I hadn’t seen done before. The twist is that the neighbors don’t want her there either and the living white people around her are actually more dangerous than the dead guy on the property. And that opens the door to talking about things like racial covenants, and the difficulty that African Americans had in getting mortgage loans, and the incredible violence that often accompanied attempts at being the first black person to move into an all-white block.

Once I started, I would find stuff that would fit really well and other times it would be a specific thing that might be a good seed for a story. It’s really piece-by-piece which came first. I didn’t want to do that thing where you make a fiction yarn a vehicle for all the cool research you did. Take the research and do something interesting with it that enriches the story that you’re already planning to tell. It also became another way of giving the characters depth and a different background. So for example, I knew I wanted to go back somehow and tell the story of the Tulsa riots, to help explain how Atticus’ father became the kind of guy he is and why his half-brother George is not nearly so angry. A lot of that was driven by the need to explain how the characters were different.

What constantly surprised me honestly was how every time I thought I understood something, the reality would turn out to be worse than what I was putting in the book. Going back to Letitia, at that same time that she is moving into that house and having the neighbors threaten to burn the place down and throwing cow patties at her front door, there was a housing project in North Chicago that had just admitted nine black families which touched off riots that went on for a year until the families finally all moved out. As horrible as what happens to Letitia in the story, it’s almost tame compared to what these real families went through. You had people bringing in dynamite from Indiana to blow up people’s houses to get rid of them. Reality always trumps fiction in the end.

RUD: Did you write Lovecraft Country with some of the current racial unrest in mind?

Ruff: I don’t know if I was that directly influenced by that. I would nod my head in recognition of that at times. This stuff never really stops going on. It’s just that there are high points in the overall fight for civil rights and equality and every time a big victory is won, white people tend to want to believe it’s over and say “okay, now we can go on and be happy together,” while in the background a lot of the stuff continues to happen. It [the book] may feel very timely, but really you could have written this story at any time post-1950s and it still would have resonated. More people will probably hear about it now and people will read it because we are more receptive to history than was the case even recently.

RUD: How did you react to the news that HBO, Jordan Peele, Misha Green and JJ Abrams were interested in adapting your book into a series? Do you get to have a role in the making of the show or is it pretty much out of your hands?

Ruff: I’m still bouncing off the walls about that. It’s very gratifying. Obviously, in the back of my head I always had the idea the book would serve as a proof of concept that the story really could work as something that is engaging, interesting, and honest, but not depressingly so. That is the hardest thing to pitch about a story like that, because you’re talking about a weekly show about the horrors of racism, which sounds kind of like Schindler’s List: The Series, and the natural response of some TV execs is to ask, who’s going to tune in to that? But the focus of the story isn’t suffering, it’s about the struggle to get through the day in a world that is set against you, and that can be a really amazing and heroic story while still telling the truth about what it was like.

What was so wonderful about getting on the phone the first time with Jordan Peele and Misha Green is they got exactly what I was trying to do. My timing for once was perfect. This was before Get Out came out, but Jordan was working on it, and I remember when I first saw the trailer, I started laughing my head off and I said “oh, so that’s why he’s interested in Lovecraft Country, he’s working on the same basic concept” and it just kind of got better from there. It’s been a great thing and I still don’t quite believe it. Watching on Twitter as the filming starts in Chicago and seeing things that I dreamed up in a room talking to myself years ago now coming to life like this is just amazing. I’m very happy.

I am a consulting producer which basically means that if they want my input on something then they are welcome to call me. I did send a lot of my research material to Misha when she first started working on the pilot. Whether they’ll want more from me, I don’t know yet. Either way I’m happy. It’s in good hands and I think it’s gonna be really exciting. If you haven’t seen Misha Green’s Underground, it’s streaming on Hulu right now and it’s a great show, you should check it out while you’re waiting for Lovecraft Country. It’s very much on the same wavelength.

RUD: Can you say anything about projects on the horizon for you? Any teasers for your next novel?

Ruff: I am not ready to talk about it yet, but I am working on another novel and I have a deadline on January 2nd. So, Christmas is going to be exciting [laughing]! I will be more able to talk about it then, but for now I don’t want to jinx it.